To people on the other side of the aisle: We have a problem.

Strong opinions opposite to my own strongly held opinions, fired off bluntly and with a claim of certitude, make me defensive and anxious. Or call it uncomfortable, disrupting, or destabilizing.

I discover in myself a knee-jerk reaction, an impulsive drive to convince the other person of my truth, in order to restore my sense of harmony and understanding. Couldn’t we all just get along? But it isn’t working. The other side isn’t buying my logic, and I’m not buying theirs, so we’re stuck, polarized and frustrated. And problems remain unsolved. We aren’t hearing each other.

A Facebook friend recently challenged an article I posted because I thought it was grounded, responsible, and well-reasoned. She called it “a one-sided hit piece where facts are not put into perspective” and “politics disguised as facts.”

Her comments “triggered” me, and I made an initial conciliatory response: “we obviously are viewing the world through different lenses. I can respect your right to your opinion, but I disagree with your premise.”

I hoped for a quick “agree to disagree” closure. But she wasn’t done. She wanted to strengthen her argument. I wanted to back away. I have a lifetime habit of seeking to escape angry confrontation, because I learned that strategy as a small child, in the midst of a whole lot of angry confrontations. Some people learned the opposite tactic as little kids, and their experience taught them that they feel better if they come out swinging, that the best defense is a strong offense.

Me? Sometimes I just want to hide. That doesn’t mean I’m conceding the point the other person is proposing.

And it doesn’t mean I’m stupid. I just feel safer going in my cave for awhile, nursing my own strongly held views to myself, because their logic measured against the sources of information I’ve come to trust over a long time just doesn’t make sense to me. And because I don’t believe the other person is going to suddenly see things my way. The sources of information they trust come from a very different set of assumptions. They’re not stupid either. And I’m not powerful enough to make them “see the light” I see in a brief interaction. So I pull back.

Each of us is hard-wired to use our habitual tendencies as our primary mode to act in the world. We might be pugnacious or retiring, intellectual or emotional. We’re not obtuse, and we’re not dumb. In order to survive a lifetime of difficult problems, we use strategies we’ve been practicing for all that time. We come to believe our strategies are the “right” way, because they work for us—and/or maybe the ways they aren’t working aren’t readily apparent to us.

Our political views, and ways we present them, are powered by that hard wiring.

Our personalities are constructed kind of like a house is built, starting from the ground up, when we’re very, very young—before we have words to formulate what is happening to us. Before the concrete foundation of a house is poured, the “main” plumbing and electrical systems are laid down to connect the house to the sources of power and water. Then as the walls go up those wires and pipes are further connected to wall switches and plugs, and to the sinks and toilets and tubs. By the time the house is “livable,” all that stuff is hidden under the floors and behind drywall, so we don’t notice it, don’t think about it anymore. It doesn’t change without some serious demolition and re-installation, so if it’s “faulty” from the beginning, there might be some difficulties along the way.

My own hard-wiring was installed during an early childhood of being emotionally neglected, ignored, and abused, and my individual response from the time I was little was to protect myself by going inside my shell like a turtle.

Once I started school I discovered my teachers were reliable sources of the acknowledgement I’d been missing. So I came out of my turtle shell to develop my intellect—to get my needs met where there was a higher likelihood of support. I learned to use words, and to gauge whether my audience was receptive. My automatic tendency today, if my intellectual or conciliatory response isn’t heard, is to pull back from a fight. And automatic strategies aren’t easy to change, without serious demolition and re-installation. Even then, they persist.

Of course this post itself is an example of my effort at intellectual conciliation. Go figure.

Somebody else’s hard-wiring may have been installed during early years of encouragement for staking a claim for the “high ground.” Maybe their early role models’ examples demonstrated that a combative stance meant they’d come out of a conflict the victor. I can’t blame them for following a strategy they learned to get their earliest needs met.

And it’s not an either-or proposition. Those two examples are polar opposites, but we are complex individuals, our views and habits shaped by a million variables starting from babyhood and reinforced over all the years of our experience.

And then there’s confirmation bias. Here’s what Wikipedia says about that:

“Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or strengthens one’s prior personal beliefs or hypotheses. It is a type of cognitive bias. People display this bias when they gather or remember information selectively, or when they interpret it in a biased way. The effect is stronger for desired outcomes, for emotionally charged issues, and for deeply entrenched beliefs.”

Google and Facebook play on confirmation bias by feeding us search responses that correspond to our search history—so over time I get fewer and fewer pieces of information that might contradict what perspectives I already hold. When I do “research” on the internet I’m not getting all the information there is, and even “information” is what has been interpreted and expressed by a writer with a particular perspective.

Much as we’d like to believe it possible, “truth” does not emerge as a sudden shaft of light beaming through the dark clouds with an angel chorus announcement. It’s not that easy.

Having said all that, let me come back to the original impetus for this post.

My Facebook friend didn’t mean me any harm. She was disturbed by the political article I posted because it challenged what she believes, in the world-view that makes sense to her. She wanted to share her views on it. And her way of presenting her views was disturbing to me. I got triggered. I posted conciliation, she posted resistance—which I imagined came from her hard-wired mode of defense. Which triggered me further.

It happened at the end of a long day of coronavirus stories, and dealing with a difficult family dilemma that has no resolution in sight, and feeling isolated, economically vulnerable, fearful about the future of the world and our society, missing my reassuring routines. In that moment I was exhausted, and my coping was frayed to shreds. I wanted to go to bed, but I was unwisely still scrolling on Facebook.

My Facebook friend stirred up all the feelings I’d been ignoring and repressing and pretending weren’t a problem.

But I was having a problem.

I was having a microcosm of the world’s most gigantic problem, it seems to me. The problem of coming to an interaction with personal beliefs held ferociously like a shield, to ward off the challenges of the other. We don’t approach political discourse or negotiations with an intention to understand. Our primary stance is to protect what we already see as truth, anticipating the other will harm us. We don’t presume a positive intention.

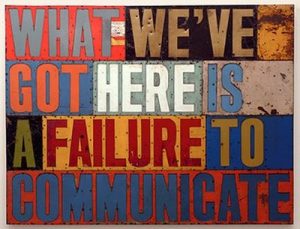

I wasn’t hearing my Facebook friend, and I don’t think she was hearing me. Not the way each of us was intending, or needing, for real communication to happen.

I was hearing the urgent press of knee-jerk, habitual response to personal historical experience. An old, old voice inside, the voice of self-protection, was setting off an emergency alarm, a signal to go to ground. Duck and cover. Run! Hide!

I wasn’t hiding from my Facebook friend. I was hiding from the ancient, painful experience of not being heard. It was old hard-wiring.

Momentarily overwhelmed and pessimistic about the likelihood of resolution, I blocked my Facebook friend. Which must have made her mad, understandably so. Maybe I was too hasty. But did I want to reopen that conversation?

How quickly are we, as a culture, blocking opposition views from our conversation? There’s a whole lot of shouting going on, and precious little listening.

Each of us, even those on the other side of the political divide, is trying to make sense of life’s difficulties. We all want to feel safe.

We want freedom, and resources, and community, and we want an easing of what disturbs us. We all want to be heard.

Can’t we all just get along?